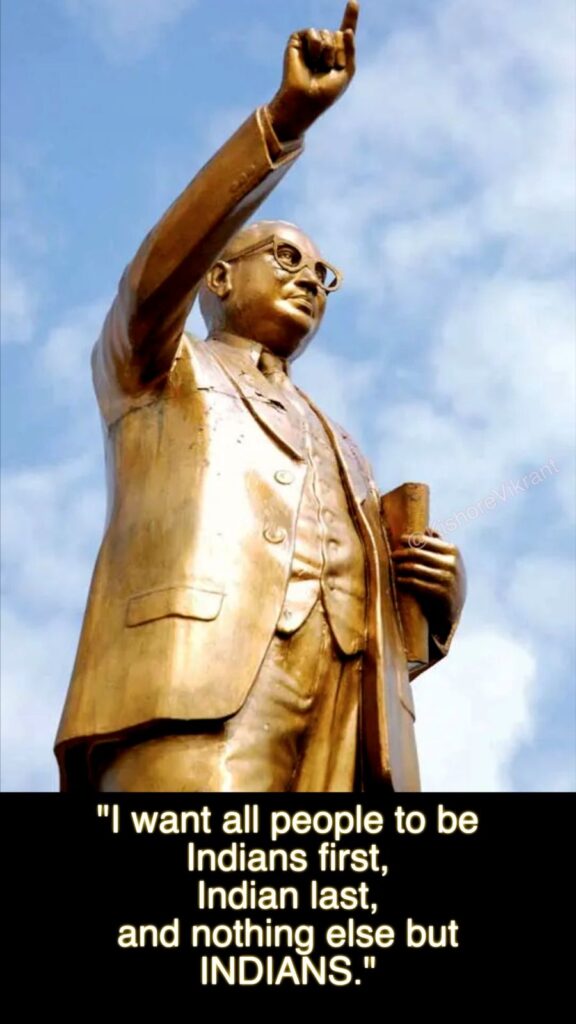

Over the past few years, a remarkable shift has taken place. From Indian streets to university campuses abroad, from parliamentary speeches to protest banners, Dr B. R. Ambedkar’s presence has intensified. His name has become a rallying point for those demanding dignity, justice, and equality. Statues of Ambedkar are no longer confined to Dalit bastis or Ambedkarite strongholds. They are being erected in global cities like Melbourne, London, and Maryland as symbols of resistance, remembrance, and moral clarity. The greeting Jai Bhim now echoes far beyond Maharashtra, spoken with pride by anti-caste organisers and Ambedkarite thinkers across the world.

This growing reverence has unsettled many. Some try to contain him as a ceremonial figure, brought out on April 14 or featured in government brochures and publicity material, while others respond with open hostility. Casteist forces cannot bear Ambedkar’s moral authority, nor the way he speaks directly to those whom history has tried to silence. The desecration of Ambedkar statues has become a recurring feature of this backlash, with reports of vandalism increasing each year, particularly around his birth anniversary. But each act of hatred only strengthens his place in public memory. Each attempt to erase him only confirms the power of what he stood for. In the twenty-first century, Ambedkar is not just enduring, he is rising. And no other political figure in India today commands the same kind of grassroots reverence, critical engagement, and moral force.

Ambedkar does not belong only to Dalits or the oppressed castes. He belongs to anyone who believes that justice must not be selective. He belongs to those willing to challenge systems, not just sentiments. His work is not a token of representation, it is a framework for transformation.

This is also the reason why Ambedkar evokes fear and hatred among the bigoted and the powerful. He unsettles them, not with dogma, but with reason. Not with sentimentality, but with structure. He spoke not only for Dalits, but for for women, labourers, for minorities, and for the dispossessed. His interventions were never half-hearted. He did not beg for reform, he demanded justice.

What makes Ambedkar stand apart is not merely his identity or background, but his method. He did not romanticise victimhood. He asked difficult questions, of Hinduism, of capitalism, of nationalism, and of power itself. His critique was sharp, but his solutions were even sharper. He led the drafting of the Indian Constitution not as a symbolic gesture, but as a functional framework designed to hold power to account.

It is easy to remember Ambedkar as the architect of the Constitution or the first Law Minister of India. But we must remember him also as a thinker shaped by a rigorous global education. He earned doctorates from Columbia University and the London School of Economics, and trained in law at Gray’s Inn in London. At Columbia, under the mentorship of philosopher John Dewey, Ambedkar developed a sharp vision of democracy, equality, and rights, not as abstract ideals, but as actionable principles grounded in social realities.

He engaged deeply with liberal, socialist, and ethical philosophy, drawing from thinkers such as J. S. Mill and Karl Marx, whose ideas on liberty and inequality informed his critique of caste and power. Above all, it was the Buddha’s teachings that shaped his ethical and political outlook, leading him to embrace the Dhamma as both a personal conviction and a public philosophy. For Ambedkar, the Buddha’s emphasis on rationality, compassion, and social ethics offered the most coherent foundation for building a just and humane society. It was not merely a spiritual turn, but a deliberate rejection of caste-based religion, and a conscious adoption of a way of life that affirmed dignity, equality, and critical inquiry.

He was attentive to systems of oppression across the world and understood that caste in India shared structural similarities with race-based segregation and other forms of institutional exclusion. While his writings focused primarily on caste, his analysis of graded inequality can be meaningfully situated alongside global struggles against group-based discrimination, including racial injustice. He remained clear that dignity was non-negotiable, no matter where one lived.

Ambedkar’s work for women also deserves more than passing mention. He was one of the earliest national leaders to demand equal rights for women in the spheres of marriage, property, and employment. His work on the Hindu Code Bill, though defeated at the time, laid the foundation for future reforms in women’s legal rights, and demonstrated his insistence that social justice could not exclude half the population.

Ambedkar also warned us that caste was not confined to geography. It was a way of thinking, so entrenched that even education, migration, or exposure to liberal ideas often failed to undo it. Today, as someone based in Australia, I have seen how caste has travelled with people. Even in countries where Indians rightly speak out against racism, they often remain silent on caste. Some even practise it, in housing choices, social invitations, marriage decisions, or workplace bias. The contradiction is glaring. Caste discrimination continues to appear in indirect but damaging ways, from universities to tech companies, from family WhatsApp groups to religious gatherings. There have been some recent gains, recognition by institutions, awareness campaigns, and the courage of individuals who have spoken out, but this is only the beginning. Much remains to be done. If anything, Ambedkar’s warning has come true, caste is not simply about place, it is about mindset. And unless we confront it wherever it manifests, the work he began remains incomplete.

In many ways, Ambedkar belongs in the same breath as Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela, not simply because of their shared pursuit of justice, but because they each turned personal pain into political clarity. All three were vilified in their lifetimes, and all three are now selectively celebrated. They were not saints. They were human beings with anger, with disappointment, with strategies that sometimes failed, but their legacy was built on persistence, thought, and action.

Ambedkar’s relevance today lies precisely in this combination of moral clarity and political pragmatism. He was not interested in quick-fix solutions. He asked Indians to examine themselves honestly, to confront caste not as a ‘social evil’ to be condemned in words but as a structural reality to be dismantled through law, education, and moral courage.

The troubling fact remains, India continues to fail Ambedkar. Manual scavenging still exists. Dalit students still die by suicide. Inter-caste marriages are still met with violence. The so-called lower castes are still kept out of power, still treated as ‘quota candidates,’ still expected to be grateful for crumbs.

But this failure also shows us why Ambedkar cannot be reduced to a commemorative moment. He must be read, heard, and engaged with, especially by those who benefit from caste hierarchies, knowingly or unknowingly. His demand for dignity, for equal opportunity, and for a rational society is not just a call for the marginalised, it is a demand that the privileged rethink their comfort.

Ambedkar teaches us that democracy is not just about elections. It is about accountability. It is about fraternity, one of the most forgotten values in our public life today. Without fraternity, liberty becomes selfishness, and equality becomes a slogan. Ambedkar reminded us that unless we learn to treat each other with respect, no legal reform would be enough.

On this birth anniversary, I do not want to remember Baba Saheb Ambedkar only through celebration. I want to thank him. For showing generations of us that it is possible to speak back to power, to fight caste without apology, to build arguments instead of seeking blessings, to walk out of injustice with your spine intact.

Ambedkar’s life was not a tale of individual triumph. It was a map for collective change. That is why he must be remembered, not just with flowers, but with fire. Not just through words, but through action. And most importantly, not just by the oppressed, but by every Indian who claims to believe in equality and justice.

We owe him that much.

Jai Bhim!