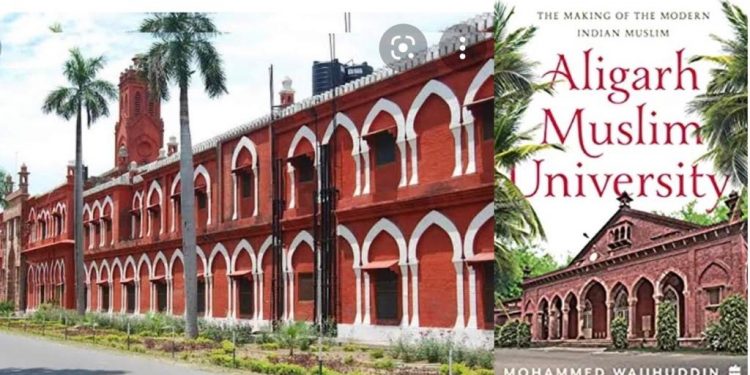

In his book on the Aligarh Muslim University, Mohammad Wajihuddin examines the role of the institution ‘in the making of the modern Indian Muslim’. Excerpts from the book.

The Inheritor of Sir Syed’s Legacy

Before we move to the post-Partition era of AMU, we must look at the life and times of Sir Ross Masood, Sir Syed’s only grandson, an AMU vice chancellor who had infused the campus with scientific temperament. He is the one about whom the poet Hali said ‘Sir Syed had donated [him] to the community’.

The night was dark and cold. A man took his teenaged son to an orchard near his house in Aligarh and began teaching him how to plough. The boy’s mother panicked and sent for a family friend to bring the boy home. The friend covered the shivering boy under his warm overcoat and had him sent home. The friend then spent rest of night listening to the boy’s father’s lecture on the need to promote agriculture in India.

The boy was Ross Masood, son of Syed Mahmood and the only grandson of Sir Syed. The family friend who rescued the boy from his torturous ‘education in agriculture’ was the MAO College British principal, Theodore Morison. On Ross Masood’s mother Musharraf Jahan Begum’s request, Morison took custody of the boy. Masood would grow up into a tall, handsome man who epitomized class, dignity, decorum and intellectual integrity. A true product of the Aligarh Movement, he carried the best values of the East and the West.

Knowing Ross Masood is akin to understanding the Muslims of India in the crucial period of the second and third decades of the twentieth century. As vice chancellor of AMU (1929– 1934), Ross Masood embarked on fulfilling the vision of his grandfather, Sir Syed, who had said with great hope, ‘Science shall be in our right hand and philosophy in our left; and on our head shall be the crown of “There is no God but Allah and Mohammad is His Messenger”.’1 As the only grandson of Sir Syed who had imbibed the values the grand old man of Aligarh epitomized, Masood represented the modern, forward-looking community Sir Syed had striven to create. It therefore makes sense to know the man and his work in some detail.

A Modern Institution or Madrassa?

If you walk down the tree-lined road from Bab-e-Syed at AMU’s southern periphery to Centenary Gate on the university’s northern boundary, you may bump into many young sherwani-clad bearded men. It is not that the sherwani or beard is a new fashion fad on the campus. They have always been there. In fact, sherwani and the Aligarh-cut white churidar for men have been a sort of uniform for formal occasions for ages here.

But in some quarters, the opinion is that they are more visible because of an increasing number of madrassa students joining courses at AMU. Many first-time visitors may mistake the campus for an advanced madrassa. Maulvis who have already acquired some learning in the Islamic religious texts enter the mainstream secular courses courtesy a provision in the Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act, 1981.

Follow NRI Affairs on Facebook and Twitter for latest updates.

Section 5(2)C of the Act mandates the university to “promote educational and cultural advancement of Muslims in India”. A committee headed by a former pro-VC, Prof Mohammed Shafi, was set up in 1986 to recommend steps for implementation of this section. Among other things, the Shafi Committee suggested that a centre be established to carry out the mandate in the Act.

So, how did AMU, a modern institution over which founder Sir Syed had faced strong opposition from the maulvis in the last quarter of nineteenth century, become a magnet for madrassa-educated students? Many on the campus hold two former vice chancellors – Saiyid Hamid and Lt General (Retired) Zameer Uddin Shah – responsible for opening AMU’s gates wide for the maulvis.

The Tablighi Footprint

The knock on the door was gentle. As I opened it, I saw four or five kurta-pyjama-clad bearded men in skull caps standing before me. ‘Asalamu alaikum,’ said the leader of the group, holding out his right hand to shake. This was the first time I had ever seen members of the Tablighi Jamaat, or preachers’ party.

I was an eleventh-standard student and had recently joined Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) in 1985. The leader of the group standing outside my hostel spoke softly and sermonized briefly. He said that life on this earth was transitory. The real life lay in the hereafter and we had to prepare for that life. The preparation had to be done while we lived here. And then he invited me to my hostel mosque. More out of curiosity than devotion, I accompanied the group.

We knocked at a few more rooms, the leader of the group mechanically repeating the rehearsed lines about life’s transitory character and the permanent address we all are destined to get in the hereafter. Since we were meeting students, many examples set in student life featured in the talks. So, this life is like an examination hall. Our performance here will decide our grade of life in the hereafter. As the time for maghrib, or evening namaz, approached, we moved to the hostel’s mosque. After the farz, or mandatory three-unit evening prayer, a middle-aged man with a flowing beard stood up and asked the worshippers to stay back for a while after finishing their remaining prayers. Some heeded his call while others finished their remaining prayers and exited. Those who stayed back were requested to move forward and sit close to each other.

The middle-aged man who began speaking to this group of listeners was the ameer, the head of the jamaat or party of Tablighis who had come from outside the town. Speaking softly, the ameer stressed the need for making sacrifices in Allah ki raah (God’s way). And the sacrifices included those of money and time. No, the Jamaat doesn’t collect any chanda or donation. They never say they want money because a mosque has to be built or some poor need to be fed. They never express concern for illiteracy, poverty, unemployment, drug abuse and so many other ills that bedevil the community.

The book ‘Aligarh Muslim University: The Making of the Modern Indian Muslim’ by Mohammad Wajihuddin is available on Amazon platforms.