A statue stolen from India in 1913 is returned to a temple in Varanasi after an artist finds it in the vault of a Canadian art gallery.

A statue of the Goddess Annapurna, stolen from a temple in Varanasi more than a century ago and taken away to a far-off province in Canada, has recently been returned to India. The story of its journey is a fascinating one considering the repatriation may not have happened if an Indian-origin artist had not chanced upon it by accident.

Divya Mehra, a Canadian artist from Winnipeg, was invited to stage an exhibition last year at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in the Saskatchewan town of Regina. So, out of sheer curiosity and interest in museum exhibits, she began to research the collection in the gallery that had been built around the collections donated to the Regina College by a lawyer named Norman MacKenzie in 1936.

This was when she came across mention of a sculpture thought to represent Lord Vishnu. Piqued about the presence of such a sculpture in a Canadian museum, she began to go through MacKenzie’s papers and discovered how he had stolen the sculpture from a temple on one of his visits to India.

Alarm bells went off in her head when she saw that Edgar James Banks, known as the inspiration behind the fictional character of Indiana Jones, was known to MacKenzie. Banks have often been accused of selling antiquities to American museums when he was a diplomat posted in Baghdad.

Divya was subsequently permitted to look at the statue, which was still in the vault. She was sure it was not Lord Vishnu but a female goddess. She needed corroboration from experts to correctly identify it.

“So, I reached out to a few different folks that I know, including a curator at the Peabody Essex Museum, who correctly identified it. I spoke to John Hampton, interim CEO at the MacKenzie, and I requested that the statue be repatriated,” she said while speaking to Artnet News.

John Hampton, who happens to be the first indigenous leader to be appointed as the executive director and CEO of the MacKenzie Art Gallery, is of the view that “repatriation is essential for museums to move forward,” readily agreed to return the statue to India.

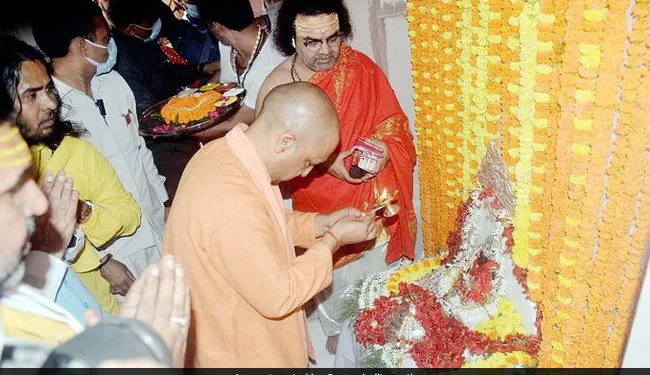

The statue of Goddess Annapurna was packed up and sent back to Varanasi at the end of November this year.

Divya was so moved by this discovery; she decided to title her show at the museum “From India to Canada and Back to India (There Is Nothing I Can Possess Which You Cannot Take Away),” which dealt in principle with “the West’s obsession with simultaneously defining and consuming the histories and identities of other cultures”.

The story of how the Annapurna statue was stolen from Varanasi is no less scintillating. Dictated ledgers belonging to Norman Mackenzie tell us how he embarked on world trips in 1913 with his wife after his considerably large art collection was destroyed by a deadly tornado in 1912. He hoped to rebuild his collection with art from all around the world.

A large leather-bound book containing pictures and detailed descriptions of each treasure he collected thereafter tell us about his trip to Varanasi and his discovery of three statues covered in vermillion (sindoor). He instructed a local to steal one of the statues and bring it to him.

To his horror, the man brought all three. Norman knew it was a serious offence and that he would get into trouble with the British colonial government when it came to their notice, so he took just one and returned the other two back to the temple.

“This is the idol that I saw the people worshipping…and is a good sample of the type of idol which is used by the poorer classes,” MacKenzie wrote in his ledger.

Now that the statue has been returned to the rightful owners after 108 years, the Saskatchewan art gallery is investigating the other 2,000 pieces in its collection, hoping to return more valuable pieces of art to where they came from.