Affirmative action in India is a constitutional right. Then why does the Indian diaspora rally against it?

The Indian population in Australia is in no way a monolith, neither linguistically nor ethnically. It is quite self-evident though that one cause unites a large majority of us away from home – an unwarranted loathing for affirmative action (reservation) policies guaranteed by the Indian constitution to India’s protected communities.

This piece, though it may seem like it, is not an attempt to cast aspersions on any particular community from India. This is an effort instead to help Australian people of Indian origin, understand themselves better. “Merit” is an often discussed and debated term in Indian-Australian circles. All Indians that settle in Australia as residents, get their “merit” re-affirmed by a points-driven, skill-based, and invite-only settler system at the screening stage itself. That kind of validation is quite aspirational in global communities that are non-white. It is especially aspirational in communities of Indian origin though.

Us neo-settlers have a keen sense of what is in store for us as we go about finding our feet here in Australia. It is a strange sort of internal conflict. Derived out of leaving behind an unequal society stacked in our favour, in search of further prosperity in a society that attaches a higher degree of dignity to labour. Well, at least most kinds of labour, exceptions notwithstanding. This phenomenon has been widely studied. The struggles of the diaspora have been exhaustively researched and written about. There are numerous support groups that actively advocate for non-white settler rights. There are numerous academic and journalistic mouthpieces too that rigorously speak to this phenomenon amongst other things. Thus, these spokespeople also form a key lens for white and Indigenous Australia to understand South Asia. And therein lies the problem. How can they realistically trust this prosperity-seeking settler population to speak authentically on behalf of those they have left behind. What was stacked in their favour back home in India, is also stacked against someone. And these settlers have seamlessly appointed themselves as spokespeople for those they oppress.

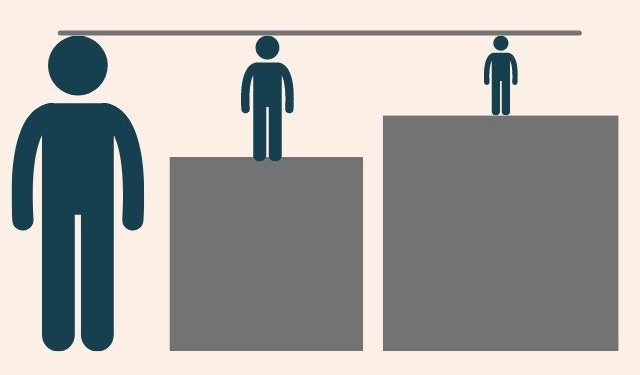

There is an urgent need for Australia, especially Indigenous Australia, to figure this out. What socio-economic (emphasis on the socio) is the Indian-Australian diaspora derived from, from back in India? What is their role back home as a culturally and financially affluent minority? Less than 15% of Indians, irrespective of their religion, are grossly over-represented in most public and private institutions back home. They own most large and small businesses, land, and media. This kind of apartheid was quite apparent at the time when the Indian constitution was framed. The 1931 census of India had revealed that around 9% of Indians were tribals (nomadic/semi-nomadic/de-notified) or first-nation people (the Adivasis). They were hardly represented in any public or private institution. Close to 16% of Indians were reeling under the terrorizing practice of untouchability. These oppressed communities (Dalits or Scheduled Castes) were equally under-represented, if not more. This left the constitution makers with a dilemma. How do they help these communities find their feet in a society that caste their dignity, or the lack of it, in the accident of their birth? To remedy this dilemma, 22.5% constitutional quotas were introduced for these communities in all public jobs and tertiary education institutions. 22.5% quotas for about 25% of the population – a population that had been treated abhorrently for over two thousand years then.

The Caste system complicates Indian society further though. The first backward classes commission of 1955 found that there were other communities too, other than Dalits and Adivasis i.e., that were also under-represented in most institutions of the Indian society. Communities that were not necessarily oppressed by the then outlawed practice of untouchability; but were still caught in cycles of indignity enforced upon them by inherited social status. Two further public commissions – the Mandal Commission (1979), and the Sachar Committee (2005) – identified communities across faiths that were close to absent from public administration and bureaucracy. The Mandal Commission termed these communities the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and assessed their share in the population to be close to 52%. The Sachar Committee in 2006 further advocated for “lower” caste Muslim communities to be added to this classification, concluding that the representation situation of most Indian Muslims was at par with Dalits and Adivasis. Muslims made up approximately 14% of India’s population then.

The Mandal Commission, when implemented in 1990, brought a constitutional guarantee of 27% quotas in public jobs for this huge section of under-represented Indian population (OBCs). The same quotas were applied to tertiary public education in 2007. By which time, it can be logically assumed, two generations of post-colonial Indian OBCs had already lost representation that was fair-and-square their constitutional right. Under-representation does not exist in a social vacuum though. If there is an oppressed, there is of course an oppressor. And these oppressors are the ones that are in majority in the diaspora now. They use their cultural and financial wealth to gain trans-national mobility, and move abroad, and cry hoarse against a policy that is empirically more than fair – 49% quotas for 85%+ of the population.

Read: Under the Mango tree

For caste-groups that have lost generations after generations to social and cultural exclusion, how traumatic it must be to see their oppressors articulate to the world that their suffering does not deserve reparations. The caste-system however, much like any other system of social apartheid, has evolved with time. In a liberalized and globalized world economy, the Indian “upper” castes, making up less than 15% of India’s population, have found easy access to well-paying private jobs and high-fee private education (in India and abroad). And as the Indian economy has increasingly privatized over the past 3 decades, share of public jobs in the total employment pie has fallen below 5%; and that of public education in the total tertiary education pie has fallen below 30%.

An oppressor-caste Indian-elite’s pettiness in crying over such a progressive policy is quite gob smacking. 49% of all public jobs make up less than 2.5% of all jobs in India. 49% of all public university seats make up less than 15% of all university seats in India. Which makes it self-evident that an anti-quota stance is less about explicit selfish interest; and more about an internalized antagonism for communities that us oppressors just don’t consider worthy of a seat at the proverbial table. This is exactly why the proverb “Indians take their caste with them everywhere”, is so colloquially used. It does not paint a complete picture of our sinister attitude though. Oppressor-caste Indians take their hatred of Dalits, Adivasis and OBCs with them wherever they go. And it is not founded simply in losing 2.5% of all jobs or 15% of all college seats to reparation policies. It is founded in a faux superiority complex that we disguise inside our assertion of the idea of “merit”.

Mudit Vyas is a graduate research student at Monash University. He studies representation in creative industries like the media and sports.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial views or position of NRI Affairs.