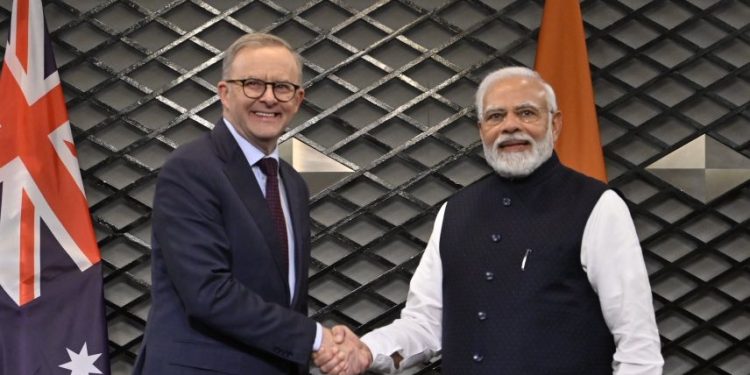

Last September when Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was in Bali for the G20 Summit, he tweeted, “So wonderful to see my friend @narendramodi, Prime Minister of India.” Modi returned the compliment and confirmed that Albanese will visit India twice in 2023.

The first of those visits occurs this week. It is a fair assumption that Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be confident that there will be no awkward questions from Albanese on the many human rights scandals swirling around Modi’s leadership.

It is only just over a month since the BBC screened a two-part documentary about Modi’s role in the 2002 anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat and other scandals engulfing the leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party. When asked at a press conference about the serious allegations aired in these documentaries, the Australian prime minister did not engage with the substance of the question, choosing to emphasise that there would be “positive discussions” with his counterpart.

Australia’s foreign minister Penny Wong, in India last week for the latest G20 Summit, when questioned about the same matter used similar soft, non-committal language.

Since both Australia and India are officially committed to media freedom, the de facto banning of a documentary on the Gujarat riots is only one of many human rights concerns that Albanese and Wong should be taking up with their Indian counterparts.

Modi’s BJP government is vigorously pursuing a Hindu nationalist agenda that now dominates various aspects of government policy. This agenda is echoed by a major section of the media and has begun to affect the legal system too. Muslims, Dalits and other minorities have to contend with discrimination and violence, including rape and murder. In some cases, members of minorities groups have been evicted from their homes.

Last year, a report by United Nations Special Rapporteurs stated that some of the house evictions had been carried out as “a form of collective and arbitrary punishment against the Muslim minority and low-income communities for alleged participation in inter-communal violence, while authorities reportedly failed to investigate these incidents, including incitement to violence and acts of intimidation that contributed to the outbreak of the violence”.

Kashmir, the only majority Muslim region in India, has been a focus of these discriminatory policies. Gregory Stanton, the founder and president of Genocide Watch, has warned that “the Indian government’s actions in Kashmir have been an extreme case of persecution and could very well lead to genocide … So many of the early stages of genocide are already present.”

If similar statements had been made about the Chinese government, Wong would have quickly raised the matter publicly and through numerous diplomatic channels.

Australia’s degree of inconsistency in dealing with international human rights issues has been revealed, probably inadvertently, on the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade own website.

DFAT’s China country brief states, “Australia raises a wide range of human rights issues with China including freedom of expression, freedom of religion, treatment of political prisoners and ethnic minorities (including abuses in Xinjiang and Tibet), torture, the death penalty, and the rights of legal practitioners and civil rights activists. Where appropriate, we also raise our concerns at multilateral fora such as the Human Rights Council.”

A similar statement would clearly apply to India. But DFAT’s brief for that country does not even mention the word “human rights”. The 1,600-word document is effusive in its praise of India and in promoting financial relations.

“Freedom of expression” identified as a key human rights issue by DFAT with regard to China is ignored by the Australian government in its interactions with India. This is despite the fact that many journalists, academics, students and unionists, who have criticised Modi or his policies have been targeted by law enforcement. Some have been held under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, the J&K Public Safety Act and the National Security Act.

In 2020, UN Special Rapporteurs found that the UAPA contravenes several articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. A key criticism of this law is that it is extremely difficult for those charged to be granted bail. Before 2014, the year Modi was elected, the use of the UAPA law was negligible. Between 2014 and 2020 over 10,000 people have been arrested under this law. Thousands have been under pre-trial detention for years. The Public Safety Act is misused in a similar way.

In Jammu and Kashmir, since 2019 when the Modi government removed erstwhile state’s autonomy and brought in direct rule from Delhi, these laws have been increasingly used to stifle dissent. 46 per cent of those arrested under the UAPA are still in jail. For those detained under the PSA, 30% are still inside.

The comparison between Australia’s response to China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims with India’s treatment of Kashmiris highlights that a commitment to human rights is not the driving force in determining Labor’s position on foreign affairs matters.

In 2018, when Wong was the shadow minister for foreign affairs, she called on the Coalition government to increase pressure on the Chinese government over the reported mass detention of Uyghur Muslims. In 2022, Wong, now Australia’s foreign affairs minister, spoke with her Chinese counterpart about Uyghur human rights on a number of occasions.

Over the same period, Wong has not spoken publicly with any level of detail about the status of the human rights of Muslim Indians and other minorities or the abuses occurring in Jammu and Kashmir.

One has to go to reports from human rights groups to ascertain information on the disturbing rise in discriminatory practices and human rights abuses occurring in India.

Human Rights Watch’s 2022 India Report states, “The government’s Hindu majoritarian ideology was reflected in bias in institutions, including the justice system and constitutional authorities like the National Human Rights Commission.” This report details how the Modi government has stepped up its attempt to curtail the work of civil society activists and independent journalists. Politically motivated criminal charges are regularly used to silence those who expose or criticise government abuses.

Amnesty International’s India Report details how caste-based discrimination and violence against Dalits and Adivasis continues unabated.

India’s friends and well-wishers internationally have an obligation to counsel the Modi government to act against hate speech, protect human rights and repeal laws that are steering the country away from the status of a secular, democratic nation.

It is time that the Australian Labor government adopted a consistent approach in its dealings with countries where human rights abuses are on the rise. This would help ensure that Australia adds its voice to the increasing number of countries speaking up to protect the rights of Indian minorities.

Wong and Albanese should note the frank exchange at the Universal Periodic Review of India’s Human Rights record. For example, Italy, the Netherlands, Britain, Canada and Angola have raised concerns about the worrying increase in hate crimes in India. Ireland, Mauritania and Greece have called for India to develop a “culture of religious tolerance”.

South Africa was more specific, calling on India to “hold accountable public officials who advocate religious hatred”. Germany, South Korea and the US reiterated their concerns about how the UAPA is being used to limit public engagement. The UN Human Rights Council is now waiting to hear from India on what recommendations made during the Periodic Review they will adopt.

Pressure is building on Modi and the BJP from many quarters. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has urged Modi to remove the “discriminatory” law that makes it easier for refugees of all the subcontinent’s religions, except Islam, to become citizens of India.

The annual report of the US Commission on International Religious Freedom identified that religious freedom conditions in India have “experienced a drastic turn downward”.

A majority of European parliamentary members backed a resolution critical of what they call the “fundamentally discriminatory” citizenship policies of the Modi government.

These developments come at a time when the Modi government’s policy of Hindutva – that promotes religious supremacy in a nation populated by people of all faiths – is becoming more discredited. The pressure on India through bilateral and multilateral channels, to reform discriminatory laws, is building.

None of this is written to criticise Albanese for talking up his friendship with Modi. But the rising tide of opposition to the policies of Modi and the BJP within India and globally clearly demonstrate this needs to be an honest relationship where the Australian Prime Minister has the courage to speak up publicly and loudly for human rights for India’s minorities.

First published in The Wire.